Henry H. Bagish

October 30, 1991

Since I’m sitting around at home convalescing from eye surgery that I had yesterday, and will be home for a little bit. I thought I might use this time to tape some of my recollections of the early history of Santa Barbara City College for the SBCC History Project for use in the archives. What I’m going to do is go through some old files, and a personal journal that I have been keeping for many years, and just pull out a few things here and there that relate to the school.

I’ll start with my initial contact with what was then Santa Barbara Junior College. In 1951 I was teaching at Glendale College. We were having a reduction in force because enrollments were dropping all over the state. I was eventually given a leave of absence. Knowing this was coming because I was low man on the totem pole in terms of seniority at that school, I was looking elsewhere. I came to Santa Barbara, the town where I had gone to school and which I loved dearly, and on March 8 interviewed with William Kirchner, who at that time was Principal of Santa Barbara Junior College. He indicated that there might very possibly be an opening at the Junior College. I talked with him about an hour. He encouraged me to file an application, which I did that very day with the City Board of Education. At that time Santa Barbara Junior College was part of the City Schools.

In May I was notified by the CTA Placement Office that I could have an interview with somebody from Santa Barbara Junior College. On May 9 I was interviewed by Roy Soules, who at that time was Director of the Community Institute (I’ll tell you what that is in just a moment), and by William Kircher, Principal of SBJC. The interview went very well, and on May 29, I received a telegram in Glendale offering me a teaching position in Philosophy and English, at a salary of $4,650 a year (not a month). The telegram was sent by Einar Jacobsen, City Superintendent of Schools. I obviously took the position, and began my career with Santa Barbara Junior College.

Let me say something now about the Santa Barbara Community Institute. I’m looking at a letter dated July 13, 1951, from William Kircher. Santa Barbara Community Institute was part of the Santa Barbara City Schools. The letterhead reads “Santa Barbara City Schools”; under that “Santa Barbara Community Institute”, and under that the actual meaning of “Community Institute”: “Junior College, Adult Education, and University Extension coordinated in a unified program”. That was the place of the junior college at that time: part of a three-part organization that combined those three levels.

We were located at 914 Santa Barbara Street. That was where the administrative office was, and a few classrooms. We also had another building one block down at 814 Santa Barbara Street with, as I recall, three classrooms. That is where I taught, in Room A; and there was also a Room B and a Room C.

My teaching schedule that was proposed by Mr. Kircher in that letter was as follows: One class in Philosophy 6A, one in Sociology 1A, one in English 1A, one in English 50A, and one in History 17A. These were all to be Monday-Wednesday-Friday classes because we did not offer classes on Tuesdays and Thursdays; you can see that would have been quite a schedule of classes.

Pulling out some material from my Journal, I see that on September 6 we had a meeting of new teachers (for all City Schools), and later on there was a somewhat longer meeting with Mr. Kircher, Mr. Soules, and the other new teacher at the JC, who was John Miles Flynn, who taught Business courses. The three of us met in the afternoon to go over procedures, etc.

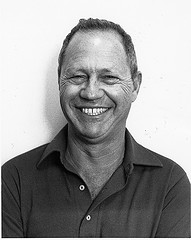

Now I’m looking at a photograph, the only one I know to exist of Junior College faculty for the year 1951-52. I’ll tell you who is in it, and I’ll eventually submit this photograph to the Archives as well. In the front row from left to right, we have Bruce Van Dyke, who is still a well-known figure in the area of horticulture. He was teaching horticulture to, as I recall, veterans. I believe he was being paid by the Veterans’ Administration. It was a special program under the G.I. Bill. Bruce Van Dyke writes a horticulture landscaping column for the News-Press. Next to him is John Miles Flynn in Business, then Laura (“Frankie”) Boutilier in English, who I know had been teaching English before that as well, I believe on a part-time basis. I had known her when I was going to school at UCSBC. She stayed with us at SBJC a number of years, then left, went back East and married her childhood sweetheart, Fred Hackett, and is now back in Santa Barbara with Fred and living at the Samarkand under the name of Laura Hackett. Next to Laura is Winifred Lancaster, certainly well-known here in Santa Barbara, then on the end of the front row is Bill Kircher, the Principal. He is mostly bald, a quiet conservative guy. He is wearing a double-breasted suit; I will say more about him later. In the rear row, we have Frank Fowler who died a number of years ago. He was head of our Theatre Arts program. Then there is myself. I guess I did end up teaching History, Sociology, Philosophy and English that year. Next to me is Philip Chauvin, who also, along with Bruce Van Dyke, was teaching some Horticulture classes for the Veterans. Next to him is Maxine Waughtell, teaching at that time Anatomy and Physiology. Maxine was with us for many years and I am quite sure that Maxine had been there before I came as well. Next to Maxine is Bob McNeill, who also was an administrator with the Junior College for a number of years.

On Monday, September 10, we had an enjoyable faculty meeting. It was a small meeting; there were only eight of us, plus Mr. Kircher. It was very informal; everyone talked whenever he felt like it .We joked around a lot; I noted in my journal that Frank Fowler addressed Mr. Kirchner as “Principal”.

The I met my first classes. I found them to be pretty much the normal kind of JC student that I had grown used to at Glendale College. The only one I found to be atypical in any way was my Sociology class, because it consisted of “all girls” (that’ the term I used back in 1951). They were all in Nurses training; at that time both Maxine Waughtell and I were giving academic classes to the student nurses being trained at Knapp College of Nursing. In fact, Maxine and I were considered to be on the Knapp College of Nursing faculty as well as on the Santa Barbara, Junior College faulty. I taught them Sociology and Psychology, and Maxine taught Anatomy and Physiology. That was a fairly large group, as I recall. I found that talking for five hours straight was a chore. The lunch “hour” was only 35 minutes; one had to gulp down one’s lunch quite rapidly. We were on the high school schedule. Classes were approximately 50 minutes in length, with bells that rang at the end of each class. At least I was able to use the Tuesdays and Thursdays to rest up from the tremendous chore of talking for five straight hours on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

That first semester I ended up teaching Philosophy, Sociology to the nurses, and American History. On October 17th I addressed the entire student body in an assembly. We had assemblies in the Alhecama Theatre; at that time it was possible to get our entire student into the theater. I as introducing the student body officers, because one of my chores on the side was Student Government Advisor. My memory of it is that we had 162 full-time students at that time.

Wednesday, December 19, the last day of school before vacation, was devoted to a Community Institute program, with attendance compulsory; a form of compulsory in-service training. Although it contained such things as harpsichord music, lectures, and so forth, I found it very dull.

On January 18, 1952, I finished up my finals, and learned that I would probably be teaching Economics as well the next semester, which would make five different preparations all together. That’s what happened. I was working very hard to keep up with five different courses, three of them brand new. I found that every night I was busy preparing lectures for the following day. It was rather grueling. Back then it was not a matter, as it is today, of whether you would be fully qualified in your specialized area. Then it was not even a question of “can you teach this?”, but rather “we need someone to teach this. It will look good for you on your record. It will expand your horizons, etc.” And so tossing Economics at me was, despite the fact that I was scarcely qualified in the field, not unusual for that time.

I complained that out of a monthly salary of $365.00, after all the deductions were taken out, including income tax, retirement fund, and summer pay deductions, that I had a take home pay of $205.30.

Here is my journal entry for Tuesday, May 13, 1952: “A shock at faculty meeting – it is likely that Mr. Kircher will be replaced next year. He announced it himself, and I learned afterward the reason is incompetence. A shame when he has only four years to go until retirement. It does not bode well if true. I like an inefficient innocuous administrator, one who leaves me alone and gives me the freedom that I desire. A replacement over-eager to demonstrate his “competence” might prove to be a nuisance. It proved to be prophetic.

On the afternoon and evening of Friday, May 23, we had a student-body beach party out at Hendry’s Beach. We had volleyball, a fire, hot dogs, beer (you can be sure that no one was watching us at that time), songs; a good time was had by everybody, and it was fun.

On Friday, June 13, 1952, we had the last faculty meeting of the year; I noted that it was a good meeting. We reviewed the year, we discussed problems and our plans for the following year. We also met Dr. Leonard Bowman, the new Director who (quoting from my Journal) “seemed quite impressed and told of his new plans. For example, sports, complete with coach, for next year. Basketball and swimming at least. Choral groups, etc. Sounds good, he seems nice and everyone, including myself, was reassured.”

Some more random memories of the campus on Santa Barbara Street, of what life was like at that time. I remember that to keep myself going on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays for that long period of time, I needed to eat something (I think we had a seven minute break between classes) and I would bring fruit from home – a banana, an apple, or something like that, and madly try to gobble it down to give myself enough energy to get ready for the next class. No cafeteria, of course; we all had to “brown-bag” it, and eat lunch within the 35-minute lunch period.

After my first year, we were able to obtain a volleyball net, a ball and standards for the net that we erected right outside my classroom, room A at 814 Santa Barbara Street. There was an open area there. That was our on-campus P.E. program. Since the volleyball court was right outside my classroom, I was in charge of the volleyball. I soon found that I could only allow games in the short period between classes. Otherwise, if there were people playing while I was trying to teach a class, the noise made it impossible. So I had to confiscate the ball as soon as class time began. It was just a quick kind of pickup game, which was indeed fun. But I still remember arousing the ire of one or two students who did not want me to snatch the ball back when it was time to teach class.

We had no library at all at that time for the college, and so I had a collection of some of my own books, and perhaps others as well (I’m not sure) that I kept on shelves in my office right next to Room A and that became the College Library. I lent books out of that library.

It may have been another year or two later, as the college began to grow, that we needed more classrooms. We obtained the use of an old wooden building on the corner of Santa Barbara Street and De La Guerra, on the ocean side, I guess the southeast corner. I remember Julia Bramlage teaching Spanish there. I remember I taught an 8:00 a.m. class there; it was terrible, I didn’t like getting up that early. We also obtained the use of another building for classroom use, around the corner on De La Guerra Street, a couple of buildings down. I think there may have been some kind of Art classes taught in there. We also had access via a driveway to a little area in back of our complex at 814, for use as a parking lot, at least for the faculty. I remember I bought a 1955 MG, the one I still drive, and I still remember parking that around in back. Students, of course, parked on the street – we did not have anything in way of a real parking lot. There was a little tiny driveway up around the administrative offices at 914 but that probably held fewer than 10 cars. The students parked out on the street, and we seemed to manage all right. We were known as the “Sidewalk Campus” or the “Sidewalk College” because we certainly did not have a real campus in the ordinary sense of the term, with lawns and all the rest. However, there was a lawn in back of the 914 buildings, in a little quadrangle with the Alhecama Theatre in the back.

We had an interesting variety of students back in the very early days. We had the entire range of abilities, I suppose, like we have today. We did have a number of flunk-out students, those who flunked out of UCSB and who were trying to make up their grade point average so they could return. We had, for some reason, a number of fairly wealthy students from families out in Montecito and elsewhere, who also came to the junior college. Even then we had a number of people from what was known at that time as the Mexican-American community. There weren’t many blacks, but some: Neill Wright stands out in my memory. I don’t remember any foreign students at that time.

As I have mentioned on other occasions, the college in a sense was starting from scratch. My memory (and I may be wrong on this) was that John Miles Flynn and I were the first two people hired on full-time contracts in an attempt to begin building the core of a full-time faculty that would build a real college. My understanding (and you may check with some of the other people who have taught part-time before I got there, on whether I am correct on this or not) is that the people before that year were either hired on a part-time basis (may have been a part-time contract) or else were working on special contracts, such as Bruce Van Dyke and Phil Chauvin teaching G.I. Bill veterans. But John and I, I believe, were the first two who were hired on a full-time contract basis. John stayed for a number of years, I don’t remember how many; finally he went elsewhere.

We did not have a college organization in place yet. For instance, we had no real registration. We had to create all of the procedures that today are taken for granted (because they are already established). Registration, for instance, became a matter we had to figure out ourselves – how to somehow get students, once they came to the school, organized into classes, how to get them registered. We had to actually devise forms which were then printed up in triplicate; the student would fill out the three sections – name, possibly address, name of course, and name of teacher. The student probably kept one copy, one copy went to the teacher, one probably went to administration. I still recall working on the design for a large box with lots and lots of pigeon holes in it where we then put the various cards as they came in from the students when they signed up for classes on registration day.

I was the student government advisor for some years there in the early years, taking the student body officers on field trips. I remember taking them down to student government conferences at Coronado, and other places as well. The student body was fairly active – especially once Dr. Bowman arrived, because he was really keen on extra-curricular and co-curricular activities. We became more and more active.

In those days, teachers were expected, and indeed we expected ourselves, to dress up. Men wore jackets and ties and pants – and I might add, shoes. Women wore not only, of course, dresses, but stockings as well (required). It was a much more formal kind of thing back in those days. Women faculty were expected not to smoke, on or off campus.

Personally I don’t think that teaching itself has changed that much. I don’t know about other teachers, but I know for myself, I don’t really think that the way that I taught then was really very different from the way I teach even now. I certainly had complete freedom, and I felt that I had complete freedom to teach the way I felt best. We believed in academic freedom and we practiced it. I never felt, even in the days of Dr. Bowman, that there was any pressure on me to do otherwise. As we were pretty young (at that time I was only 25 when I first arrived), there seemed to be a closer relationship between faculty and students. Again, I was young, just a few years older than most of my students. We socialized a lot, there were a lot of parties; in fact, we were all expected to chaperone. We didn’t always adhere to the strictest of standards. Very often I would find a hand being stuck through a window at me with a beer can being offered to me. I will admit that I did partake sometimes of beer with students. Gifts from students were not all that uncommon at that time. Very often at Christmas I would receive fairly nice gifts from students, never offered in the sense of a bribe, as that would never have worked anyway. But there was quite a bit of friendship between faculty and students. I know that I frequently played volleyball with students, and because even at that time I was kind of a beach rat, I played volleyball down at the beach, and went surfing with some of my students. I remember students taking me out and teaching me how to skin dive and look for lobsters. I was introduced to surfing at the Rincon by one of my surfing students, who also took me out lobster hunting, etc. So again, we were close. I remember being invited to weddings of some of my students. And that was a pleasurable part of teaching at a very small school.

I may be wrong on this, but I believe I was the only one of the faculty back then who had taught at any other junior college; I had been at Glendale College for two years. That proved advantageous as we began to organize our own school, because most of my colleagues had no idea of how things were done anywhere else. At least I did have that experience. And so frequently I as asked, what did they do about this sort of thing at Glendale College? I know that that background helped me when we decided to form the organization that finally became the Instructors’ Association. That was true of other things as well – registration, and about anything else you can think of.

In the early years we had no Bookstore at all. Students had to go to Copeland’s Bookstore, a privately owned bookstore in the store which is immediately south of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Old Mr. Copeland was the one who stocked our textbooks and any other supplies we would need. In the 1952-53 school year, we did have a basketball team. Classes in those early years ranged from sometimes as small as 30 students on up to 60 or so, which I noted at the time was much too large. I notice in my Journal that in April, 1953, I traveled by train with Bill Dubray, who was President of the Associated Students, up to Asilomar for a conference on student government.

The coming of Dr. Bowman brought an onslaught of assemblies that he would call, similar to the kinds of things that you have in high school and junior high school; I will be commenting on some of those, and the difficulties we had concerning them, later on. One Saturday, the students held a Paisano Day at Oak Park, with volleyball, a Spanish dinner, and dancing. Overall, in the early years the students were a lot more social than they are today, being a small school; we got together quite frequently and had a lot of activities.

In 1953, I happened to catch a group of cheaters in one of my classes; I think it was a History class. Many of them were on the basketball team, and I caught them red-handed. At first Dr. Bowman had backed me up (I had told them that I would give them all F’s and kick them out of the class), but then he backed off on that; that was one of my first conflicts with Leonard Bowman.

A number of times I was able to take my small Philosophy class down to the beach, as we weren’t very far from East Beach; it was kind of neat sitting on a log with my shirt off (another time I just wore bathing trunks), discussing Philosophy with my class. This was done, by the way, with permission, taking them down there.

Also with Dr. Bowman we had a whole series of formals (gosh, you don’t hear about formals any more) and proms. We had Spring Formals, we had Christmas Formals, all done in the best social way with everyone dressed up. Of course, the faculty were there as chaperones.

For the Spring semester of 1953, Dr. Bowman had proposed a new schedule for me to teach. That would be History 17, Econ. 1A, plus Geography, which I had never taught before and in which I had no background except one brief course while I was going to school in the Army. His argument was that I ought to add this to my repertoire of courses I could teach. I protested against a schedule like that, and for once I won. I never did teach Geography. In May of 1953, Winnie Lancaster was appointed Dean of Students.

Here is an excerpt from my Journal entry for Wednesday, June 10, 1953 — “The last hectic day of classes, amidst tests and frantic last minute polishing off of units of material to be taught, Dr. Bowman finds he has to rearrange an assembly. So, despite protestations, my Philosophy class has to listen to stale jokes for an hour, and then stay after school to finish up the semester. Grrh! I was very angry. Indeed, I had to stay working at school until after 6:30.”

But on June 18, 1953, we had what I described as a really impressive Commencement out on what we called “The Green,” in front of the Alhecama Theatre, complete with caps and gowns and hoods. Apparently we did not have a Commencement the year before, in 1952, under William Kircher. This was, I believe, our first Commencement, in 1953.

The next semester we, the faculty and administration, registered students. We did not have a registration staff, or admissions staff, or anything like that. One of the things that angered us was that registration occurred before school started, before our contracts began, and we were never paid for it. That was a source of some discontent.

Here is a telling entry for Monday, September 14, 1953: “Faculty meeting – Bowman pulled some of his usual inane stunts like requiring classes to meet even with just a few present while the other students are undergoing testing.” (During these early years we did a lot of testing of our students – aptitude tests and a lot of psychological testing, that we used either for help in placement, or simply to help us understand the students that we had.) “All of this being typical high school stuff – this business of requiring classes to meet even though the students were all elsewhere, with no realization of how adults react to such rulings in college. And a few other things emanating either from him, or Dr. Jacobsen (who was the Superintendent of City Schools), for which the only word is chickenshit. Such things as time clocks and 12 month schedules were being used as threats against lack of punctuality. Or because we were complaining about injustices as having to work two days last week without pay (that was for registration). The fool, I will just have to keep still until I get tenure.” At that time I didn’t have the feeling about academic freedom that I developed after tenure!

On the first day of classes, Wednesday, September 16, 1953, I remarked in my Journal “What a big day. As students dashed about in random confusion, as new instructors looked in vain for vacant classrooms, I sat back and watched hordes of students file into my classroom. Classes of 40 and 50, filling every chair. I am sure we have broken all enrollment records. I did what I could with them oriented them for four straight hours, and another after lunch, and went home in the afternoon hoarse and exhausted.” (I had already had that time schedule for a year or two, and it remained that way for quite a while.)

Back then the College stood in loco parentis to a much greater degree than it does now. Here’s a quote from the 1953- 1954 Catalog:

“A list of available living quarters for students who are away from home is available in the Dean’s office. Students are required to have such living conditions approved by the Dean before making final arrangements. Living in apartments, except in the case of married students, is not encouraged by the College.”

I noted on September 18 that I had sold $290 worth of student body cards. The latest official figures were in – we doubled our enrollment. Another entry: I administered psychological tests in the Alhecama Theatre, full of students. I am pretty sure that was the Minnesota Multi-phasic Personality Inventory. On a Wednesday night, the students had a party dance. On Monday, October 12, 1953, we had a school dance in the afternoon. On that day we also had a campaign assembly. I was officially in charge of it, but Bob Profant actually handled the assembly itself. Apparently it went very nicely. We had packed the Alhecama Theatre and had a full house for an audience. A lot of spirit and enthusiasm. The students campaigned with posters, handbills, speeches and I note that “at last, with size, we are getting some real school spirit.”

On October 21st I had some more conflict with Leonard Bowman, who once again would not back me up in terms of my wanted to oust a cheater from my class.

This next entry is apropos because I am doing this recording on November 2, 1991 – we are still in the throes of Halloween weekend out at Isla Vista, with those shenanigans. So the entry that follows is from Wednesday, October 28, 1953: That night we had a school Halloween Party. My wife and I went in costume, as everyone did, and I wrote in my Journal that “the party was a whooping whooping huge noisy jammed success. There was a fleet of cars, over a hundred people jammed into four rooms, with a band going on in one, records playing in another, and just uproarious goings on all over. The party was far from dull. There was contagious excitement in the air, which slyly secreted spirits no doubt aided. (I was referring there not to the supernatural variety but the liquid.) With a lot of people drinking on the sly, I anticipated trouble, for it was a truly explosive situation with everyone milling about jammed tight screaming with raucous delight, but trouble never came.” Because I was there as a chaperone and adviser to the student body, I managed to squelch a few potential troublemakers, and everyone simply had a wonderful time and all went swimmingly.

Here we go with some more conflict. On Monday, November 2, 1953, “Dr. Bowman pulled a quickie assembly, an interesting science film but with a religious message that I suspect violates laws concerning separation from church and state.” I am quite sure that that was one that he obtained from the Moody Bible Institute in Los Angeles and I noted in my Journal, “I wish I were in a position to protest.” At that time none of us felt it was possible to protest such things. Later on, we did. This was followed by another one hour assembly, which Dr. Bowman called whenever he felt like it. All classes had to be cancelled, and you had to bring your students.

On November 6, 1953, I was visited in one of my large History classes by the Principal of one of the elementary schools who had come to evaluate me because I was coming up for possible tenure.

Further on that same day — “After school a meeting with Dr. Bowman and the student body officers for two hours. The student body officers, without my foreknowledge, tore loose at him violently for exerting too much control and not giving them enough responsibility, and they did this quite tactlessly. Fortunately Dr. Bowman took it well and very diplomatically and tactfully explained to them the situation, and calmed them down. So that from my point of view, the meeting was successful in that there emerged from it a better mutual understanding.” I noted that the students felt more able to complain about things than those of us on the faculty with no tenure felt able to do.

By 1953 I notice that we were playing volleyball in the little area outside my classroom. On Monday, November 23, 1953, “a good committee meeting (I don’t know what committee it was) in which Dr. Bowman sat back and listened to his faculty planning things. A good thing, I feel.” And so we were beginning to make some of our first steps toward faculty involvement in how the school is run.

There was a Christmas Formal. I note that I took tickets at a Junior College basketball game. On Friday, December 18, 1953, I not that “the last day before vacation was dispatched in a mad flurry of tests, students wild with anticipatory Christmas spirit, and a piñata breaking. A gay Christmas Party for the faculty ended it up. We whooped it up with cake, cookies, ice cream and Christmas carols and a fine sermon by Father Bowman. Wow!” I note that on Friday, January 15, 1954, I had a long day at school including a two hour session with Leonard Bowman thrashing out a student body constitution. He and I apparently sat down and wrote the constitution. An entry for Thursday, January 21, 1954: “Bowman sure has goofed. Finals begin Monday and the schedule of finals still isn’t out. The students are up in arms, unable to learn what to start studying for. And it’s completely his fault, since has taken the responsibility for the schedule unto himself. This is his one big fault – he has not learned to delegate responsibility. He makes everything, every little detail, come to him, pass through his desk and thus he has become our school’s biggest bottleneck. One man can do just so much, and he feels he has to organize and supervise and approve enough to keep five men busy.”

Monday, February 1, 1954 – “a tremendously exhausting day: registration. It was the final field trial of the elaborate system we had spent so much time working out. Of course, as with anything of this scope and complexity, there were many snafus. Some of the faculty I had entrusted with special jobs let me down.” (I guess I must have been in charge of developing this.) “And other bugs developed in the system that could not have been foreseen. Of course I had to run around like mad, trying to remove bottlenecks and straighten out problems with a hundred different things and responsibilities, so I had to be everywhere at once. Well, one learns from experience, and we learned many important lessons from this first trial. By the end of the long day having jammed hundreds of students through our procedure (what a madhouse it was), the temperature standing at 80 degrees outside in the shade – I was near collapse,” I noted.

By the Spring semester of 1954, we were filling classes with waiting lists. In February, Dr. Frank Fowler, head of our Theater Arts Department, put on “Death of a Salesman” at the Alhecama. On Friday night, February 19, 1954, I attended a thrilling JC basketball game, complete with a large crowd, decorations, cheerleaders, and a dance afterward, which, however, turned out to be a flop, I noted.

Back then we had no peer evaluation of teachers. In addition to that other Principal of an elementary school, I was observed by Dr. Charlotte Elmott who was, I believe, the number two administrator downtown in the City Schools, who came to observe me teaching (although she did give me advance warning.)

I attended that Spring a student government conference in Coronado with our four student body officers. By the way, please note that I received no additional compensation for being student government advisor and doing all of these things; this was in addition to a full-time teaching load. On Thursday, April 8, 1954, we had a talk by Dr. Jacobsen, Superintendent of City Schools, in which he painted a rosy picture of SBJC’s future – a move to the Mesa campus by Fall of 1955, with great expansion, which made us all very happy. (We did move, but to the Riviera campus.)

On Wednesday, May 12, 1954, I spent an interesting afternoon in some enchanting house high atop a hill in Summerland browsing through thousands of books and selecting hundreds of them to be purchased for the start of our own JC library. I think it was some private collection, perhaps someone had died; we were going to start our own library from that base.

On Friday, June 4, 1954, I received my contract for the following year. I was placed on permanent status, that is to say I finally had tenure, and I was to receive a yearly salary of $5,300.00, That evening we had our Spring Formal at the Montecito Country Club. I remember that Dr. Bowman had an interesting attitude about these Formals and really liked having us go to places like the Montecito Country Club. He felt it was a good experience for our students to be able to do things “the right way”. I note that on June 18, 1954, we hired a new Dean of Women. That was Marie Lantagne.

On Monday, September 13, 1954, we held our Fall Registration in the Recreation Center gym under our new Registrar. (I would have to look it up to see who that was.) A number of serious snafus developed, such as failing to have an adequate filing system set up, and running out of class tickets, just to mention a few. I managed to convince him, the new Registrar, of the seriousness of the filing situation, and we found the old system just in time. But bottlenecks occurred because of new personnel; and my History class jammed up to 49 people before the leak in the dike was plugged. “On a happier note, the selling of student body cards on a voluntary basis has already netted us almost as much as last year through compulsion.”

On Wednesday, September 15, 1954, I notice repetition of something I had alluded to earlier: “A stupid day at school – had to meet all classes despite the fact that nearly everyone was gone being tested. I met eight out of 60 in one class, two out of 35 in another, and then I had to make out absence slips for all the others.” And it was the kind of thing that just drove us up the wall.

In 1954, Bob Kelly came to join our faculty to teach History, and I finally was then able to drop from my load, and start a course in Courtship and Marriage, in addition to still teaching Sociology and Psychology.

Here is a telling entry for Wednesday, November 3, 1954 — “Bowman raised my blood pressure today by issuing an edict, still unofficial, that instructors cannot ‘coerce’ students into buying Bluebooks, which cost two for 5¢, for exams. Even though it aides the instructor enormously and the students themselves raise no quarrels about it. They are required to buy their own books and supplies, notebooks and paper and pencils. This is just another of his usual high school deals. On this one though, if he persists, there is going to be a fight. The student body officers are up in arms too, since their blue-book-supplying project is shot.” Apparently they had hoped to make money selling those blue books. “And also because of rigid censorship of the student newspaper, now little more than a “Bowman Bulletin’.”

By November 10, 1954, we had a committee on teacher load which recommended – thank goodness – that I be relieved of student government work and that it all be given to Dean Lantagne. That idea thrilled me. On November 12, 1954 – discussing student government with Dr. Bowman and its recent inefficiency, (“lack of proper coordination”) I told him that I am primarily interested in classroom teaching, not in administration. And it seemed that was what he had been waiting to hear me say. So, with Mrs. Lantagne eager to take over the job, the committee (Teacher Load Committee) recommending the change, and Dr. Bowman now aware and evidently sympathetic with my attitude, I have high hopes of finally getting rid of this student government headache. November 22, 1954: “The Student Council finally passed its budget for the semester, allotting only $300 to Athletics where $1500 had been requested. This is going to be quite a bombshell to hit Dr. Bowman. I am sure glad there are two of us faculty advisors now to distribute the responsibility. Unfortunately, the ax these days falls on poor Marie Lantagne. “ I guess I didn’t get out of it altogether, I guess I just finally got some help from Marie on running student government.

On December 1, 1954, I had an interview with Dr. Bowman which I feared would be devastating, when he appeared at the Student Council meeting obviously upset and anger over the recent shenanigans, refusing his basketball money, and introducing some constitutional amendments designed to remove some of Dr. Bowman’s dictatorial powers. The interview turned out to be smooth and sweet with no trouble whatsoever. He had calmed down and evidently Mrs. Lantagne’s presence and accessibility provides a neat buffer between him and me. (Poor Marie, she is a dear friend of mine.)

Ah, the olden days. Here is Wednesday, December 8, 1954 – “I served as escort for each of the candidates for Queen of the Christmas Ball as they paraded on show before an assembly. Beautiful, daringly gowned young ladies.” But my, how times have changed.

Monday, January 3, 1955 – this was the first day after Christmas vacation and I “taught hard all day long and lectured fast, almost losing my voice. Right after the last class, I was summoned to Dr. Bowman’s office where Marie Lantagne and I were put on the carpet, but really, really chewed out for failing to quash some radical constitutional amendments (radical in the direction of a greater democracy and student self-determination) being put for a vote by the student body officers. But we did not take it lying down; giving each other support, we upheld the students and justified our stand. All in all, it became a real emotional rhubarb. He got quite excited, putting us, of course, at an advantage. For the first time, I think, we really let him see how we felt, and the difficult position we were in caught between administrative dictates and our own desire to teach democracy. We finally agreed on a few compromises and we were saved only be a faculty meeting coming up next.” We sure had long days back in those days.

Monday, January 31, 1955 — I had a lot of problems that day. The first of which was the fact that Dr. Bowman informed me that I wouldn’t get any equipment for a new course that I was preparing called “Study and Reading Improvement”. I wouldn’t get any equipment for it at all, but I would still be offering it nevertheless. He said, “I am sure there is lots you can still do.” And I also had to listen to somebody who perhaps has never been mentioned before, Trudi Colberg. She was really, in a sense, the Business Department of the College. Now we have many people doing what one person did all by herself. Trudi was, as I recall it, a single woman who had a very forceful personality and sometimes she could be quite irritating. I note in my Journal that I had to listen to Trudi Colberg spout her side of a big blowup she had had on Friday with Marie Lantagne. Then a third problem was the student government was able to collect only a drop-in-the-bucket’s worth of money from card sales. I was given the unhappy task of trying to bulldoze those who resisted into buying them, which I did not like as a chore at all.

On February 3, 1955, we were still giving the psychological tests to students, and in the second semester of 1955 I was teaching Study and Reading Improvement. On Monday night, March 14, 1955, we had a student body skating party at the roller skating rink. I am surprised by this next entry, for Monday, May 23, 1955: We had a faculty potluck dinner to top off the teaching day. I note “my, our faculty has grown. I didn’t know many of the people there.” It certainly was a lot smaller then it is today! On Tuesday, May 24, 1955, we had what we called an “institute” (I think that was like in-service training) in the afternoon. We had some interesting discussions on tenure and on the nature of a junior college faculty. Quoting from my Journal, “I was pleased to see that Dr. Bowman is definitely developing and growing from the high school-minded administrator he was when he first came here, to a true college director, with a college outlook. No longer can anyone teach anything as in high school, where one doesn’t need really to know anything but just direct traffic, keep them busy and sit on the lid. (I have written a quote from him: “Why don’t you teach Geography, Bagish? Add it to your list.”) Now one must know their subject matter – all for the good.”

In the fall of 1955, we had moved up to the Riviera Campus, and we had our first faculty meeting on September 8, 1955. “It was quite an experience. There were so many new instructors that I felt like a stranger on my own faculty. The old ones were far outnumbered. Then Dr. Bowman proceeded to destroy the good deal I have had for four years. From now on we must be on campus five days a week, and we three-day-a-week instructors must schedule our office hours on Tuesdays and Thursdays. So I rationalized – it was good while it lasted.” We have a new History man on the faculty, Ken Shover. On Monday and Tuesday, September 12 and 13, 1955, we registered students all day long, finally quitting at 5:30. We registered all the next day as well, even though we began teaching classes. I was teaching Anthropology by now.

On Thursday, September 29, 1955, “we had our first home football game, and a real success, winning 31 – 6. We had a good team and a good big crowd, all enthusiastic and full of spirit, a really big enterprise. And to think that all this has developed out of the tiny school I joined four years ago.” I was very proud.

I note that on September 30, 1955, I had more indirect conflict with Dr. Bowman over admitting all students on waiting lists to classes, without regard to limits or the instructor’s “right to insist” (on not exceeding the class limit). “For insisting against his orders, I will probably get called on the carpet.” At this point, in the Fall of 1955, I am teaching just Courtship and Marriage, and Anthropology. In addition to Ken Shover teaching History, we also have Harry Scales teaching Psychology, Mary Farrell (I think she was there the previous year as well) teaching Philosophy, and of course Bob Casier is with us too, teaching Political Science.

I am pleased to be able to report that in January, 1956, I received total and complete support from Dr. Bowman when he, along with the President of the City Schools Board of Education, and Charlotte Elmott (who I believe was in the Number two position in the administration of the City Schools) had received copies of an anonymous letter attacking me for, among other things, my “anti-anti-communist views”. It is true that I had publicly expressed disapproval of Senator Joseph McCarthy and all of his operations, and in that sense, I could be considered an anti-anti-communist, but what I was pleased about was that Dr. Bowman and the rest of the administration supported me completely, and nothing more was ever heard about it.

Also in January, 1956, I was working hard at trying to work out a system for faculty advising of students as part of the registration process. Students would first come to be advised by a faculty member about programming and courses to take, and then the student would go ahead to register.

The Riviera campus was a big improvement over our tiny, cramped quarters on Santa Barbara Street, and with its central Quad and its reflecting pool, it had a lot of charm. However, the buildings themselves were quite decrepit. I had a long narrow classroom upstairs in Ebbets Hall which had leaky roof. When it rained the last rows of my classroom were hidden from view by a curtain of water pouring throughthe ceiling. We had a cafeteria on the ground floor, and a small faculty dining room, but the plaster was peeling, and during damp weather the plaster would drizzle down onto our food. It was quite dreary, so when it wasn’t raining, we preferred to bring our own brown-bag lunches with us to school, and sit on the sloping front lawn to eat together. We did more than eat; we sat and discussed and exchanged views on everything from politics to college matters. It became a true forum, a morale builder, and a college tradition; I would say that it really formed the genesis for what later became the Instructors’ Association, and in turn the Academic Senate.

We also played a lot of volleyball in those days. We played in our small gym, and so we had a lot of interaction that way as well. In May, 1956, we had the big Formal at the Coral Casino, but now we had progressed (or regressed!) as a faculty; I noted that some of us faculty members, before we went to the Formal, “fortified ourselves first with some vodka drinks at Louise’s” (that must have been Louise Thornton).

In June of 1956 I once again clashed with Dr. Bowman. I once more had some trouble with cheaters in one of my classes, and had given them failing grades for that. Dr. Bowman had initially said that he would back me to the hilt on the grades that I had given those students – but these cheaters had complained to Dr. Elmott downtown at the City Schools administration. Once that happened Dr. Bowman apparently could not butt heads with Dr. Elmott, and backed down again. My entry for June 6, 1956, (I was quite irate) — “Respect indeed. At the moment, all day I have been filled with only disgust. Here is the latest. At 7:45 I was bounced out of bed by the phone. Bowman wanted me at school by 7:45 with my grade book. I rushed like mad, made it by 8:00, and what I had feared came. The grades were to be changed. He anticipated and feared trouble from Dr. Elmott, that she would force the change, and he figured it would be better to beat them to the punch and change it here. I said I didn’t like it, but of course it would have done no good to defy him. So I told him what the grades would have been, and he said he would change them after telling Dr. Elmott that “we” “I” had decided to raise the grades. I walked out of there feeling like crap, betrayed, bluffed, shamed. He was scared for his job, scared of downtown, and he let me down. On the very heels of his “brave stand” yesterday, in front of witnesses, to save his neck from attack. Cheating, threats, pressure, all of these are now S.O.P. (standard operating procedure). I don’t know how I can face those gloating students when they find out. I feel like a pawn, sacrificed. Next year, however, a Scholastic Standards Committee is going to get some requests from me. We need a definite policy on grades and cheating that can’t be bluffed or overruled so easily. Ditto plagiarism and professional ethics. These students may escape but I will try my best to close up these loopholes. As for Dr. Bowman, weak sister, stooge, puppet, unworthy of the name of Director. No respect from me ever again.”

That June we had to type up what were called Courses of Study, with goals and objectives, all that educational jargon, and we had to do this for all of our courses. It was a terrible job, reminiscent of things that we had to do later on in the College’s history. On June 14, we held our graduation ceremony in the Riviera Quad, and we also held our Farewell luncheon at El Encanto Hotel, right across the street.

In September of 1956, a new school year, I see that I was chairing the Scholastic Standards Committee. I noted also that we had a Curriculum Committee. On that Scholastic Standards Committee, what we were doing primarily was hearing appeals from students who had been kicked out of school for low grades, students who were appealing to try to get back in. I also noted that semester I was teaching Philosophy, Anthropology, Introductory Sociology, and Courtship and Marriage. On October 8, 1956, I have this entry – “Dr. Scharer, the new Superintendent of the City Schools, met with the faculty of the Junior College for an informal talk. Very interesting. He made the comment that he plans to make permanent from now on, that is to give tenure, only to those with doctorates or those who are actually working on it.” And I noted that, since I did not (and still do not) have my doctorate, how glad I am that I am on tenure, and how trembly many of the new people must be as a result of that declaration. Obviously he did not go ahead to do that, however.

I note for Friday, October 12, 1956, — “the faculty, with my subversive hand pushing them, is moving toward establishing either a faculty club or a separate faculty meeting in which administrators would be excluded, so as to make possible free expression of opinions that might never be uttered in front of the administration. I think it is an important and necessary step.” I would add, at this point in history, that that was probably the beginning of an important turning point in the power situation on the Santa Barbara Junior College campus. I noted the following Monday, October 15, just this short entry – “ things began popping in faculty meeting about our little revolt, and Dr. Bowman looked unhappy, but nothing has jelled as yet.”

That was the beginning of motion in our direction of faculty independence. On October 17th, I note that I had “an after school conference with Dr. Bowman in which he discussed this latest faculty move at length. I gather that he asked me in as an old and trusted instructor, in order to communicate his views on the topic to the rest of the faculty, and I guess through me to try to persuade them to do the right thing as he conceives it. If only he knew my role in the whole affair and my own views on the doctorate, and the salary schedule. But I was discreetly silent and agreeable on those points, although bold in bringing up issues in which the faculty does want free expression and clarification.” I note for December 7, 1956, “a new controversy at school over censorship of a faculty-student publication, which as me upset as well as everyone else.”

An entry for December 11, 1956 – “Bowman upsets me, considering classroom activities secondary in importance to assemblies, and his attitude in general on censorship, etc. Grrrr!” I note that our Philosophy Club at that time was holding discussion meetings at night.

Tuesday, January 8, 1957 – “A harangue by Bowman and violent discussion on the failure of all faculty members to conform 100% in such vital collective activities as attending the Christmas Tea, joining the NEA, etc. The tyranny of the majority was brought forth forcefully.” I noted for Thursday, February 7, 1957, that I was chairing the so-called Retention Standards Committee, where we were hearing hard-luck cases of students who I guess had been dropped for poor grades, and we were hearing their appeals to be let back in. The only thing to soften the blow of that sort of thing was we mailed out our decisions rather than telling the students then and there.

On Friday, March 22, 1957, we had what I think was perhaps the very first TGIF session after school at Bob Casier’s house, where we discussed the whole theory of evolution over beer. And that was the beginning of a very important TGIF tradition of discussing philosophical issues in a relaxing way at the end of the school week.

I noted that Spring that already the Social Science Division (I don’t know if we were actually a Division as such, but our Department or Group) did have “a recommended percentage of A’s, B’s, etc., in the way of grades.” A brief note for Monday, April 8, 1957 – Bowman is giving some difficulty about the Bluebooks that the Philosophy Club wants to sell; apparently they were doing that as a fundraising activity. The next day, April 9, there was a lively controversial faculty meeting with a vote on the wording of a Code of Ethics going against Bowman’s expressed view. I noted on April 23, 1957, that we were being visited by an Accreditation Team. On Saturday, April 17, we had a school Luau at night . I was there as chaperone, and it was held in the Quad. The place was beautifully decorated. We had Chinese food, a band (what was then called a “Combo”) for dancing and it was rather a good event, a lot of fun.

An entry for April 29, 1957, indicates that apparently I must have succeeded in getting information for the Philosophy Club to continue selling Bluebooks, because I note that we went over the top in our sale of Bluebooks by passing the break-even point. So now we were even making a profit. I noted the following day, Tuesday, April 30, 1957, that after having some fun playing volleyball, there was a hot faculty meeting, discussing the accreditation team’s questions with the Superintendent of Schools (that would be Dr. Scharer) present. The meeting was very candid with many pointed questions, including a number that I had raised apparently, and with Bowman quite on the spot. It was an informative meeting, however, that I called “air clearing”. That afternoon I took the Philosophy Club that I was advising on an interesting excursion out to the Vedanta Temple in Montecito where we were able to ask questions and get answers from the Swami.

On Tuesday, May 7, 1957, I note some rugged volleyball, Casier and I against the P.E. staff which then consisted of Revis and Wenzlau. That evening we had another Philosophy Club meeting; not many people attended, but we had a religious discussion monopolized by a minister and his wife, out to make converts. On May 28, I note that Bob Casier and I won our first volleyball tournament game.

On Friday, October 4, 1957, after noting how Santa Barbara has grown, I also note “SBJC has grown too. 934 students, quite an increase from the 162 of my first year here.” On Monday, October 28, 1957, this entry – “I blew up when I learned that another Psychology class is to be sacrificed for a Rally. This time for the premiere for football money. It seems that classes are the most expendable thing at this school these days,” something that had irked me earlier. And I note two days later on October 30, “the Rally was cancelled; I feel vindicated.”

The next is a truly significant entry. Monday, November 4, 1957 — “According to Laura Boutilier, who had a candid talk with Dr. Scharer today, heads will soon be rolling at the J.C. Specifically, Bowman’s, by January 1st. Evidently considerable dissatisfaction with the way he has been running the school. Not only on the part of faculty, but also by the Administration. We shall see. Perhaps we shall soon no longer be run like a high school.” Laura, I believe, was holding that meeting with Dr. Scharer as a representative of our Junior College faculty, and specifically because she was Chairman of the famous Liaison Committee which was the ancestor of the Instructors’ Association to come, and after that the Academic Senate. I have in my possession a copy of an Annual Report of the Liaison Committee to the Faculty, signed by Laura Boutilier, Chairman. She does not mention that particular meeting, of course, but I am sure it was in connection with that job. Some of the dates on this report are wrong, and I am going to try to straighten that out, and try to square it with dates in my Journal. I will do that later. In any case, this copy of that report, which is an important one, will of course become part of the Archives (see Appendix U).

Tuesday, November 19, 1957, this entry – “At Faculty Meeting, we debated the interruption-of-classes question, at long last. And Bowman came out in strong support of our position. (A good politician knows when to jump on the bandwagon.) In announcing the forthcoming survey by the State Department (I do not remember what that was), he appeared completely innocent of what some of us understood to be the true purpose of the visit, like a lamb going to the slaughter.” I can only assume, and hopefully some other old-timer will be able to remember what that so-called State Department visit was, but I can only assume from my entry that somehow this is going to be some kind of external visit to give us grounds for having Dr. Bowman removed.

Friday, January 3, 1958 – We had just come back to school after our Christmas vacation. “The really big news broke in tonight’s paper – Bowman has “requested” a transfer to a new job of “Research Assistant” Downtown, with menial duties, as of July 1st. And a new Director, also to be over Adult Ed, will be chosen. So, all our rumors were true. Now what?”

A little bit about faculty politics, here is an entry for Monday, January 6, 1958 – “Maneuvering is now going on for the one faculty position on the Screening Committee to help select the new Director.” Apparently Dr. Norm Scharer was already providing finally for some actual formal faculty input on picking our new Director. I added after that, “Laura Boutilier, Bob Casier, Bob Profant, and I seem to be the primary eager aspirants for this important job, serving on that Screening Committee.” On the following day, Tuesday, January 7, there was a hot Faculty Meeting. Of course, in those days, all these Faculty Meetings included Administration, including Dr. Bowman – and I note that “Bowman spoke briefly on his transfer. And very well too. He said just the right things, getting us and him off the spot mostly. To the end, he was a good politician.”

I see at this point I was still teaching just Monday-Wednesday-Friday classes; I did not go on campus, I guess, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, because for Thursday, January 9, 1958, I had this entry – “First Thursday at school all semester, I believe – a worthy record. Went up for a Liaison Committee meeting with Dr. Scharer and our Administrators on the topic of teacher evaluation. It was a good meeting with free exchange of ideas.” The results, also on that day, of the nominations for that one faculty position on the Screening Committee to pick the new Director, and a surprise, was that Bob McNeill, who was an Administrator, had gotten the most votes. I put in parentheses “We think he had been pushed by the non-academic bloc to block the academic bloc.” I wish to point out that at that time there was a division on our Faculty between the academic fields and the non-academic or vocational fields. This entry is an example of that. Back to the result of the nomination. Bob McNeill, who was the Administrator in charge of Vocational Education, got the most votes. Bob Casier was next, then I, and John O’Dea. Laura, unfortunately, only got one vote. Bob Casier and I flipped a coin to eliminate splitting the academic vote, so we would only have one person representing the academic side. Unfortunately, I lost the coin flip, and so I was out of that particular race. On Monday, January 13, 1958, I noted that it was a conflict-filled day. “Dr. Scharer has thrown out the results of Friday’s election in which Bob McNeill won, because Scharer said that he intended to get a teacher on the Screening Committee; he did not want an administrator. He told Bob Mc Neill, evidently, to withdraw. So, what will happen now is anyone’s guess. There are forces pulling in all directions. Many hidden motives as well. Tomorrow’s meeting should prove interesting.”

On Tuesday, January 14, 1958, I note that in faculty meeting Bob McNeill did indeed withdraw as expected, and began to urge that Bob Casier be given the post, but Bob Profant proposed that there should be a new election with self-nominations and short speeches about qualifications, which I seconded, but that was defeated, and then Charles Courtney moved that Bob Casier be chosen by acclamation, and he was. Bob Casier then was to be our faculty representative on the Screening Committee to help pick our new Director. A very important position indeed.

An entry for Friday, February 7, 1958 – “The Liaison Committee was invited by Dr. Scharer to meet the top candidates for Director, and help pass judgment. A noteworthy step we thought” – and I still do. For those days, that was really quite radical. “We met in Scharer’s office for coffee, etc., and questions and answers. We met the first candidate (I don’t wish to use any names); he flew in from somewhere else. Someone who struck us as being very sharp and alert and intelligent, quite a change from the present incumbent.” On Tuesday, February 11, 1958, we met with the second candidate for Director, and I felt he wasn’t nearly as strong as the first one. Also that day I note that in Faculty Meeting a nasty letter to Bowman was read by the President of the CTC (which I think stood for City Teachers Club, and was the local branch of the California Teachers Association). That letter listed non-members of the CTC who were on our faculty, and moralizing how the tree is more important than the leaves which will wither and fall, etc. An approach which I didn’t like at all and I note that the faculty and I were furious, as was Bowman. Give him credit for that.

An important day, Thursday, February 13, 1958 – “We met our third candidate, Joe Cosand, presently Director of West Contra Costa Junior College, and we were all impressed to the point where we recommended him to Scharer at a candid meeting where we were all able to speak our views. In so doing, I believe we did well. Scharer plans to use us this semester in working with the new Director in planning, reorganizing, etc. It should be a fascinating semester.”

An entry for Friday, February 14 – “The latest is that the CTC, when presenting salary increase requests, will state to the Board that it does not represent the following non-members. The pressure is really on to join, conform, be a one hundred percenter. First giving a black list to the Administrators, then cancelling all group-sponsored insurance, and now jeopardizing salaries and jobs themselves.” I editorialized, “Will goon squads be next, etc.” So we had a hot noontime argument on the topic. I was in opposition to Marie Lantagne, she being opposed to freeloaders. You will note that even then we had a similar kind of philosophical disagreement on issues that remain with us even today with our current Instructors’ Association – but I don’t think anything to the point like what we had back then.

On Saturday, March 1, 1958, I went to a reception at Dr. Scharer’s office introducing Joe Cosand as our new President to our faculty. On Monday, March 3, 1958, this entry – “At a noon meeting of the instructors (not one of our standard faculty meetings), I was elected to be one of a committee to set up procedures for picking a new name for the school, and was then chosen as chairman of that committee. More importantly, we got our idea of an Instructors’ Association approved, and will now go ahead and draft a constitution, with the Glendale one as a model (one I had brought with me when I came from there). And we did it with no opposition. Very slick, a real coup, especially since we have in mind eventually, perhaps, to secede from CTC (City Teachers’ Club) and get a separate charter from CTA; on a non-unified dues basis.” This had been our basic argument with the local CTC group, which strongly stood for unified dues (which meant if you wanted to join one, you had to join all three levels, NEA, CTA, and the local CTC). Many of us were opposed to unified dues, and I remember speaking on a number of occasions on that issue.

On April 24, 1958, I finally finished off our Accreditation follow-up report, after over a year of work, so it was quite a relief. I guess I must have been responsible for writing that report. I report on April 18, 1958, that our committee had screened out five candidates for the new for the school. On Tuesday, May 13, 1958, we had a Testimonial Dinner for Dr. Bowman. On Monday, June 2, 1958, I note, perhaps immodestly, (modesty was never my long suit anyway) that I was elected to the Executive Council of the new Instructors’ Association, the one that I had first instigated (that is the immodest part of it), and I may become its first President. I also received a letter from Dr. Scharer congratulating me on the Accreditation Follow-up Report, but the letter also insisted that he refuses to approve anything that would set the JC apart from the rest of the school system. I report the next day, Tuesday, June 3, 1958, that I made it, I was elected the first President of the SBJC Instructors’ Association.

On Monday, September 8, 1958, the first day of the new school year, we had a useless general meeting, and then a faculty meeting in which “Joe Cosand showed the entire faculty the stuff of which he is made, which for me, is great.”

Thursday, September 11, 1958 – “A truly hectic day, one of the worst. A tremendous number of new students showed up for advising. Such a jam in fact that I had to clear the stairway to the Library, which was packed solid down to the main floor, by letting them all get numbers, and come back in order later in the day. I was especially harassed, having to run the whole show, answer the telephone calls, close classes, answer questions of one and all, plus advising my own students, whom I never did finish up with. Before I finally took off for a reception and a faculty meeting at Adult Ed. Never again a day like this, says Joe, and I second it.”

September 22, 1958 – I was appointed Chairman of a General Education Committee. Since I was the president of the Instructors’ Association, I had many discussions and informal talks with Joe Cosand. On October 8, 1958, I had a discussion with Joe, “on a junior college district, the plot currently close to my heart – a very frank discussion in which he mentioned that he too dislikes unified dues and NEA, and never joined the latter until this year. He is in a tough spot, but he will try approaching Scharer again on the JC district, armed with some more information and some new arguments that I shared with him.”

Saturday, October 11, 1958 – “We had a Sadie Hawkins Day Dance at school which I helped chaperone in costume.” Gosh, I wonder if anybody these days even remembers Sadie Hawkins Day. In case you don’t, that is a character out of Li’l Abner. On Friday, October 24, 1958, we had a faculty picnic, beer, and barbeque, very informal and fun, far different from past years. Back under Dr. Bowman, we certainly had no beer! I noted that I MC’d the program following the dinner.

Tuesday, October 28, 1958 – Joe Cosand and I took off for a three day conference, up at Yosemite, of the California Junior College Association, which up until then had been almost exclusively an organization for administrators. But Joe was one of the few junior college Presidents who was trying to get more faculty involvement in that organization, so he made sure that I, as President of the Instructors’ Association, got to go. He and I drove up there in his car, and it was a really neat time, because not only did I get to talk to Joe and learn about him and share and exchange ideas, but he introduced me to many people from all over the State and the nation at that conference. Joe was already widely known. I noted in my Journal for October 28 that after really getting to talk at length with Joe and learning about him and his ideas and his philosophy, I stated “he is my kid of boss and guy, right down the line.” Of course there were many meetings throughout that three day conference, and I noted that on Thursday, October 30, I attended a breakfast meeting with five other faculty association representatives, and we exchanged a lot of informal information with each other. But I noted “we were scarce though; this is truly an administrators’ organization.” There was a long morning session, resolutions to be voted on, etc. I can say that I came back from that conference with an enormous amount of respect for Joe Cosand as a man and as the head of our college.

On Thursday, November 6, 1958, there was a meeting at school at which Dr. Scharer said that a bond issue for the junior college was being considered, even by the Board. So maybe there is some hope for us after all. On Friday, November 7, 1958, I chaired the first meeting of the Instructors’ Association at noon. On Monday, November 10, we had a General Education Committee meeting that I chaired, but the meeting failed to get anywhere. It was blocked by the old basic problem of just what general education is, and what it is that we are trying to do. I remember that Tim Fetler was involved in that debate, and we went back and forth at great length. On Tuesday, November 18, 1958, I chaired a panel discussion in front of the faculty on general education. It turned out to be rather important “since it is a crucial and controversial topic. Norm Scharer, Doug White, Sam Wake all attended. I thought we were pretty rushed, having to compress long speeches into five minutes each, and since we had been through it before, I felt it was rather cold, cut, and dried and impersonal. But evidently it went over well, since attention was undivided. We received compliments afterward, which rather surprised me, including from one faculty member “Thanks for the first faculty meeting I have ever attended that was really interesting.” That was a surprise for me. I guess it was worth it. Unfortunately there was very little time left for questions so we have yet a great deal of debate ahead of us. We have only begun to open up the question of ‘What is general education, and what are we all about?” I also note that we had a Library Committee, and a member of that committee was Alice Belton, who was Librarian at that time.

I think I have straightened out the dates on the Annual Report of the Liaison Committee to the faculty for the year 1956-57, the one that is signed by Laura Boutilier, Chairman. First of all, that is the correct year, and the date of the Annual Report, October 1, 1957, must also be correct. What threw me off was the first sentence of the Report which says, “the first meeting of the Liaison Committee was held October 26, 1957.” First of all, that is impossible because that is after the date of the report itself, and of course it had to be a year earlier, and so that date must be 1956. I have made that correction on my copy of the Annual Report. “The first meeting of the Liaison Committee was held October 26, 1956. Members were Bob Profant, Harry Scales, Ken Shover, Virginia Sipe, Secretary, and Laura Boutilier, Chairman.” That was the first year for the Liaison Committee, I am quite sure; there were new members for the following year, I served on that one. That was the year 1957-58, because 1957-58 was the year in which finally Dr. Bowman was sent elsewhere, and we managed to participate in the selection of Joe Cosand. I have been struggling with what was wrong with those dates for a long time, and I think I have finally figured it out.

There does remain a mystery for me, with my imperfect memory. That is, for years I had thought the person who had gone to talk to Dr. Scharer about getting rid of Dr. Bowman, because he was just impossible, was Bob Casier, and I have said that on a number of occasions, including publicly. But all the evidence seems to indicate, according to the Journal that I kept, that it may very well have been Laura Boutilier. I would strongly urge that somehow Laura Boutilier, who is in Santa Barbara (her name is now Laura Hackett, living at Samarkand) should be contacted to try to clarify her role in that, and of course, check with Bob Casier as well, because certainly, whoever it was, and I do suspect now that it was Laura Boutilier, that was a crucial, crucial event in the history of our Santa Barbara City College. (I did contact Laura; unfortunately she doesn’t remember, nor does Bob Casier; so the meager evidence points to Laura.)

I have just finished talking with Laura Boutilier to try to refresh my memory on some points, and she reminded me that Leonard Bowman was never addressed by anyone by his first name, certainly by nobody on the faculty. He made it very clear that he was to be called Dr. Bowman, and Dr. Bowman he was. This was a far cry from Joe Cosand. I believe I asked Joe, when he came, how we were to address him and he simply said, “well, of course, Joe”. He was always Joe, and there was a world of difference between addressing your chief administrator as Dr. Bowman, or just plain Joe. It was typical of the kind of man, the new man we were getting.

On May 25, 1959, we had a debate in North Hall on the Riviera Campus. It was a debate on the question of relativism, between, on the one hand, Bob Casier and I upholding the viewpoint of relativism, and on the other hand Tim Fetler, who was our Professor of Philosophy, and Laura Boutilier, attacking relativism, promoting instead the idea of universals. It is interesting that since then I have changed my views considerably on the whole concept of relativism; I have come around, not completely, but to a large extent, to the views held by Tim Fetler.

At this point, I find that on going through my Journal, I am not getting much from my mining of that material now, and I don’t know that I will go back to that. It is conceivable that I may look for particular points later on. But at this time, once we had Joe Cosand on board, we seemed to have reached our golden age. I had far fewer gripes, and so I note that comments on my part in my Journal about problems at school were fewer, and I am not really discovering much more in the Journal, as attention is now being paid to other, personal, family things. I think maybe at this point I’ll stop that kind of chronological search through my Journal, and perhaps revert to the questionnaire from the Committee seeking ideas or recollections for the SBCC history project. I think I will simply go through some of the questions and give you some of my random responses, in particular looking at question #2, my recollection of the various Directors, Presidents, and Superintendents.

Let me remind you that William Kircher had the title of Principal, while Leonard Bowman was Director. With Leonard Bowman, frequently we had Faculty Teas at his house, where everyone was supposed to dress up very well (ladies were expected to wear hats and gloves), and of course, we drank tea. I can assure you there was no alcoholic beverage in view during those parties, nor any smoking. He was strait-laced, he was religious, and he expected the members of his faculty to comport themselves in proper ways.

Now about Joe Cosand – and I told about the coming of Joe. I was bowled over by the man, and I believe that virtually everybody, maybe everybody on the faculty was equally bowled over. Those people who came after Joe’s time may find it difficult to believe how enamored we were of this guy. It was partly, of course, because he came on the heels of Leonard Bowman, who had left a very bad taste in virtually everyone’s mouth. It was more than just the fact that he was somewhat young. I’ve described him on other occasions as a “democratic leader”. Leonard Bowman had been a stereotypical paternalistic administrator, the kind that was from the older era. But Joe was of the new breed, where instead of being paternalistic and patriarchal, he was truly democratic. He did not impose his views, he was no dictator, he did not tell us what to do, but rather when I say he was a democratic leader, what I mean by that is this: He was indeed the leader of the school, the leader of the faculty, the leader of the staff, and what he did was, when the college had a problem, instead of telling us what we were all going to do to solve it, he urged us to try to come with solutions, suggestions, ways of dealing with it.

I am thinking of one case in particular where, as usual, we were having financial problems (I guess that is always the case). We had limited resources, there was a lot we wanted to do, we had a lot of students. We also were hoping that perhaps we could get higher salaries for faculty, and he pointed out clearly enough that there is just so much of a financial pie to go around, just so much money available. You can put X number of dollars into salaries, but if you are going to put more than that, you have to somehow cut back somewhere else. You have to conserve money, save money in some other area. You can’t put all the money you want into every area. And he came up with a challenge — “What are we going to do about this? What can you suggest so that we can operate in a more economical way perhaps, so that we can put some of our scarce resources into such things as salaries, or something else?”

It was that challenge, I know, that stimulated me to start thinking about how we might, for instance, increase class size, in a way that would perhaps save the college money, but also in a way that those faculty who would then be stuck with more students in their classes would have some kind of a positive incentive to want to do that, to take on more students in order to save money, so that it would available for salaries or whatever else we had in mind. It was out of that challenge from Joe Cosand that we finally developed a large class policy. I know that I worked on that, I am quite sure Bill Miller worked on it as well, and we kicked it around, we probably had a committee about it, but ultimately we did develop a large class policy whereby faculty who would voluntarily accept a larger number of students in their classes would get more of what we now call TLUs, and that of course was more economical for the college.

Joe Cosand came to our parties, he drank beer with us, he shot the bull with the guys and the gals. He was just one of us, and there was something very real about him. We could communicate so readily with him. There was never any bullshit, if I may use that term, between us. His ideas were progressive. I found so much to like about the man, and his leadership was so fantastic, that I remember once being challenged by the late Charlie Atkinson when, after Joe left, I remarked to a gathering that I was so sad, because I really felt that I “loved the man”. Charlie thought these were awfully strong words for one man to be using about another man. But it was still the way I felt. I had, and I still have, a great deal of affection for this man who was a superb leader. I have kept in contact with Joe over all these years. We still at Christmas exchange cards and notes, and on occasions when he has come back to Santa Barbara, he’s stopped in to see us, to visit us. And of course, we have a standing invitation to see them at their retirement home in the State of Washington.

Going farther down the list of former heads of the College, I come to the name of Doug White, who was, as I recall, an interim Acting President for perhaps one semester. He had been an administrator in the City Schools, as I recall. Doug was a nice guy. I never had a complaint about Doug. He was innocuous, he didn’t bother anybody, which was a nice thing really, just a good guy.